Governance and Political Discontent

In many countries, politics is seen as a problem rather than a solution to other issues.

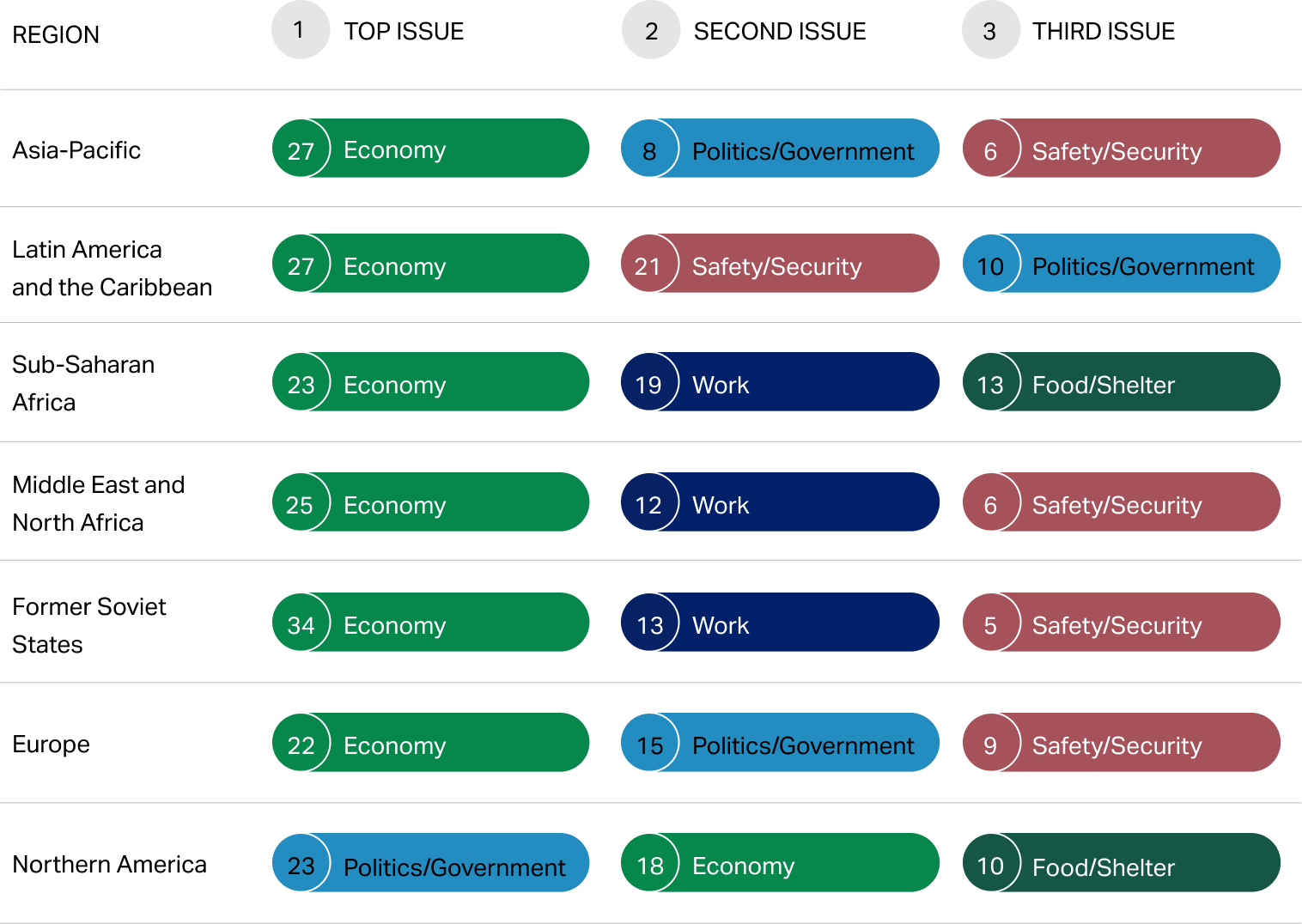

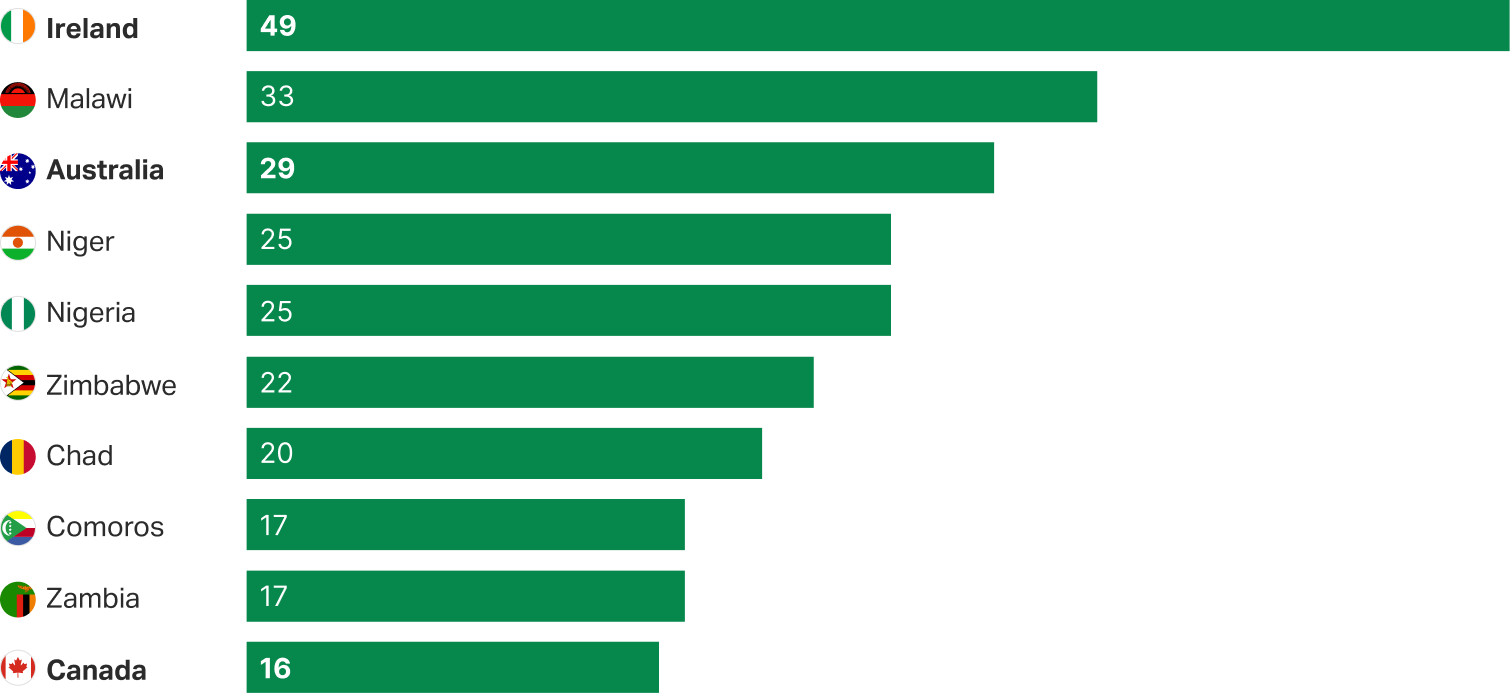

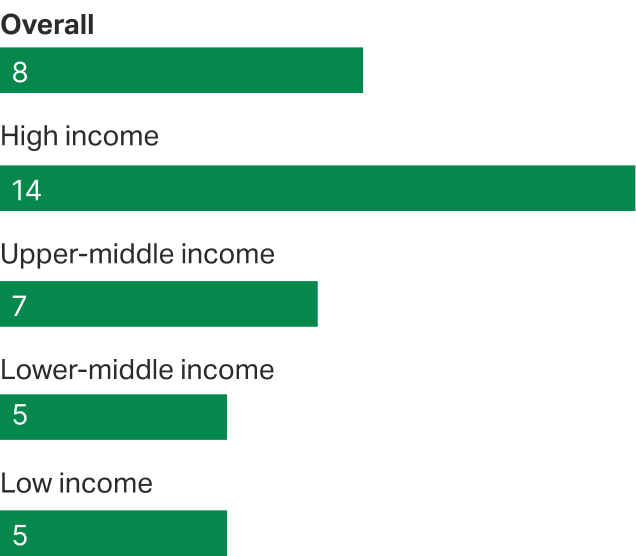

Political and governance issues rank as the third most common national concern globally, at 8%, although prevalence varies by region.

Northern America (23%), Europe (15%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (10%) all see double-digit levels of concern, higher than in Asia-Pacific (8%), sub-Saharan Africa (6%), former Soviet states (5%) or the Middle East and North Africa (4%).

Wealth and Political Concern

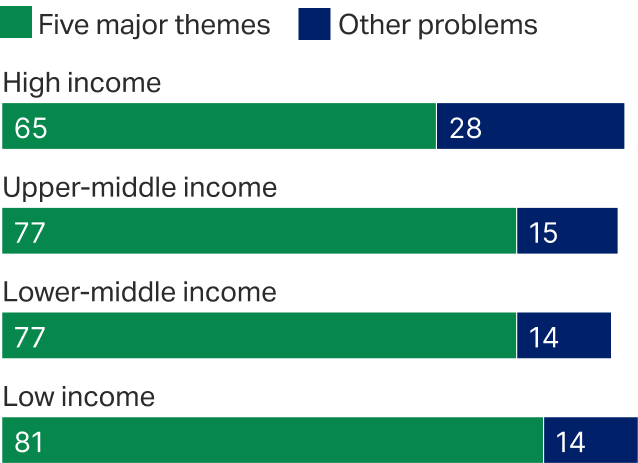

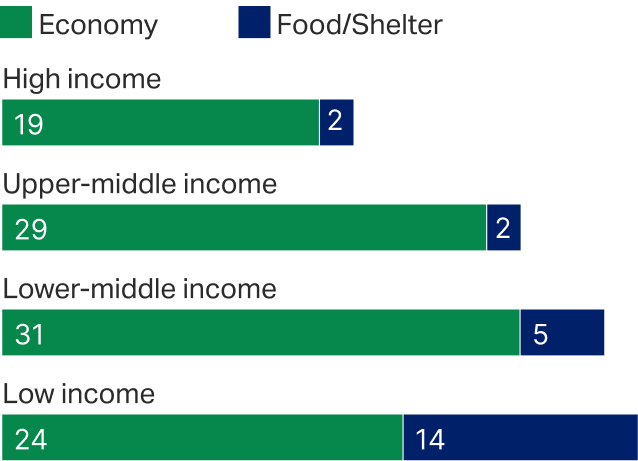

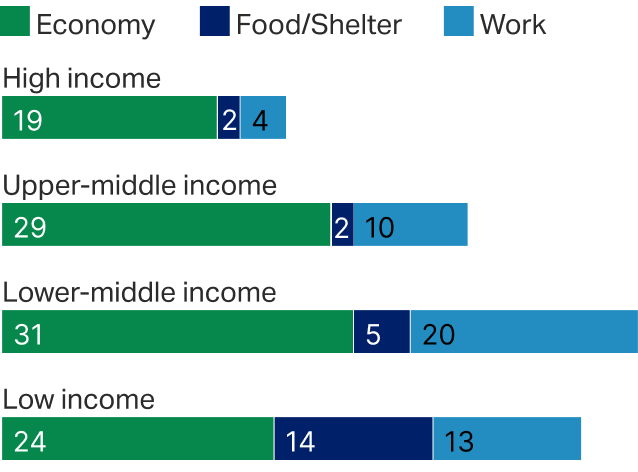

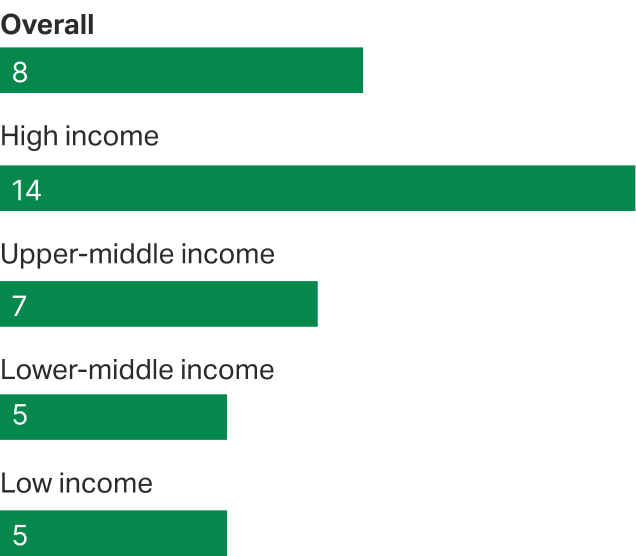

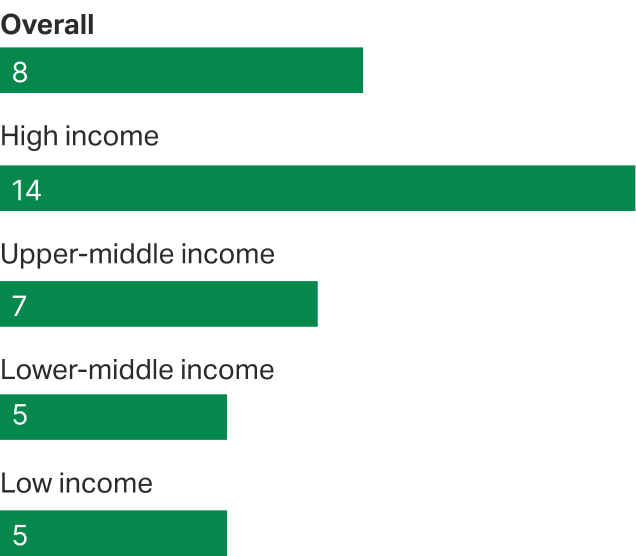

People in high-income countries are more likely to name politics as the top issue facing their nation than those in lower-income countries.

A median of 14% of individuals in high-income countries cite politics or government as their most important problem, compared with 7% in upper-middle-income countries and 5% in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

These findings demonstrate that when basic needs are more secure, frustration is often directed at the performance of government itself.

Perceptions of Politics/Government Being Top National Problem by World Bank Income Groupings (% medians)

Concern about national politics and government also rises with household income.

Perceptions of Politics/Government Being Top National Problem by World Bank Income Groupings (% medians)

After controlling for demographic factors and national income, the likelihood of naming politics as the top national issue increases with household income:

Key Insight

Nine percent of the poorest 20% name politics as the top issue, rising to 12% of the richest 20%.

Two factors help explain this pattern:

-

As societies grow more prosperous, expectations for effective, transparent governance rise faster than governments' capacity to meet them.

-

Wealthier nations typically offer more democratic openness, making criticism of government more acceptable, visible and sometimes a sign of political health.

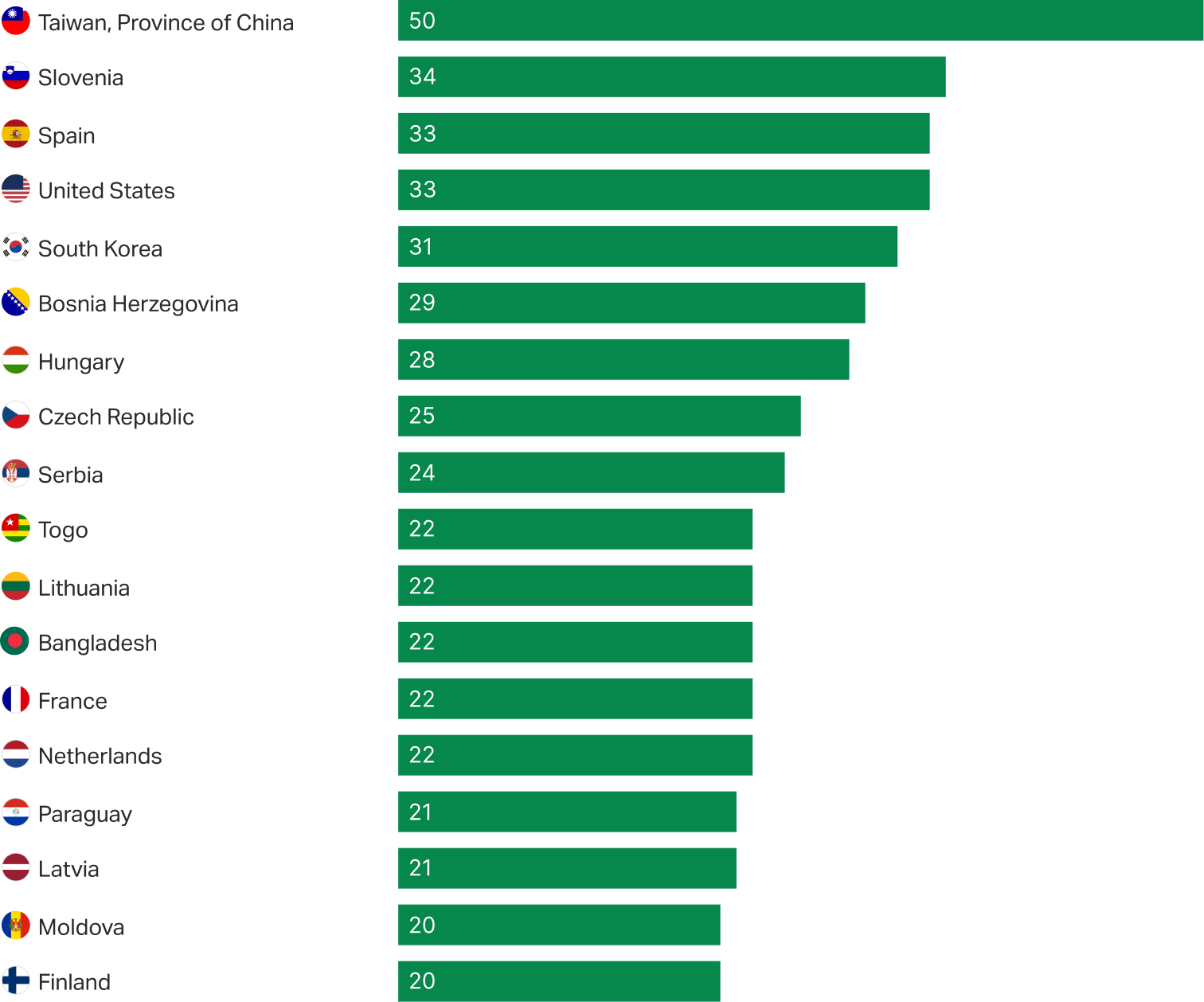

European countries feature prominently among nations and areas most concerned with political issues.

While Taiwan ranks highest globally (50%), Slovenia, Spain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Serbia, Lithuania, France, the Netherlands, Latvia, Moldova and Finland all rank among the countries most likely to cite politics and government as the biggest national issue.

The Trust Connection

In many countries, trust in institutions has become a barometer of perceived national wellbeing.

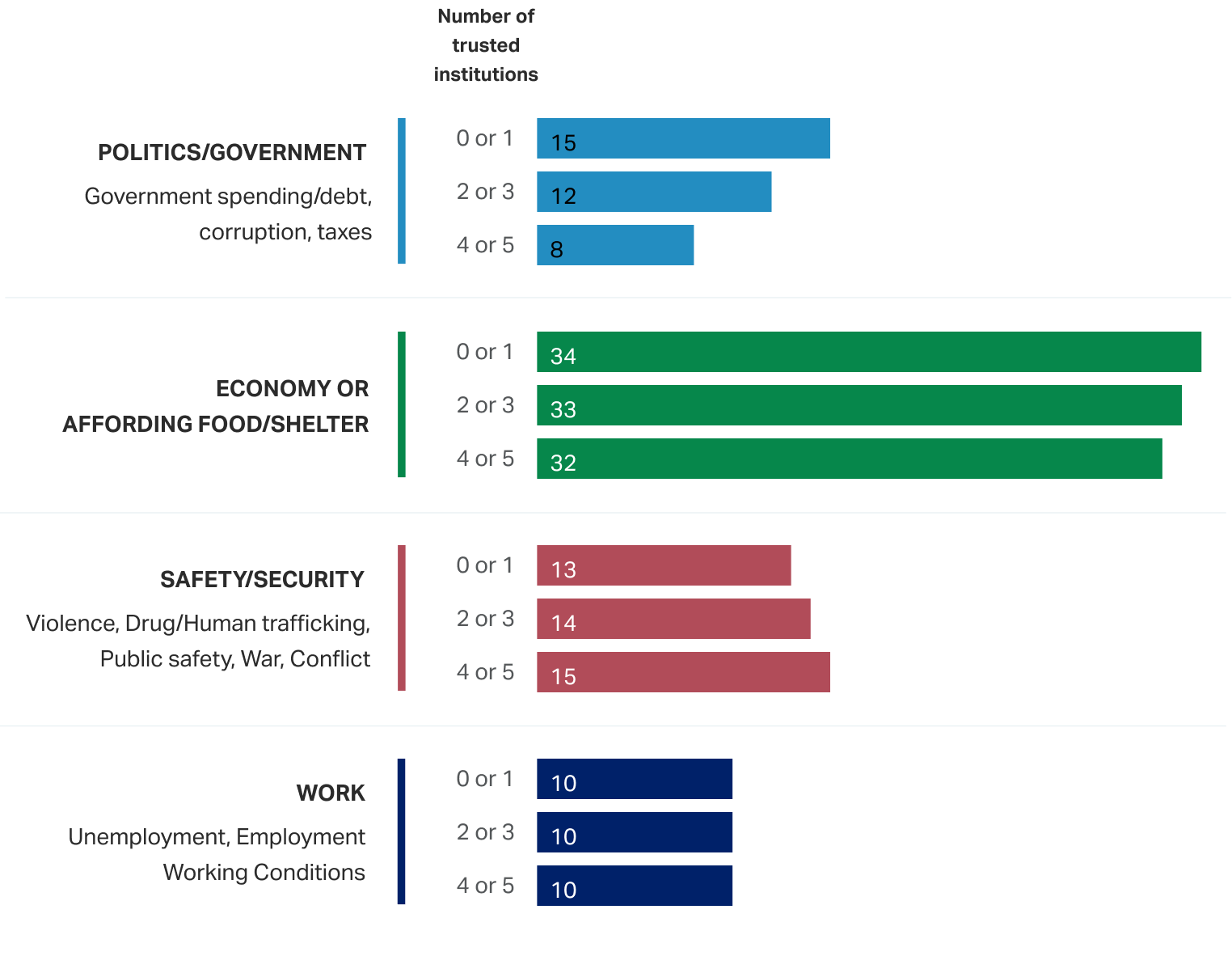

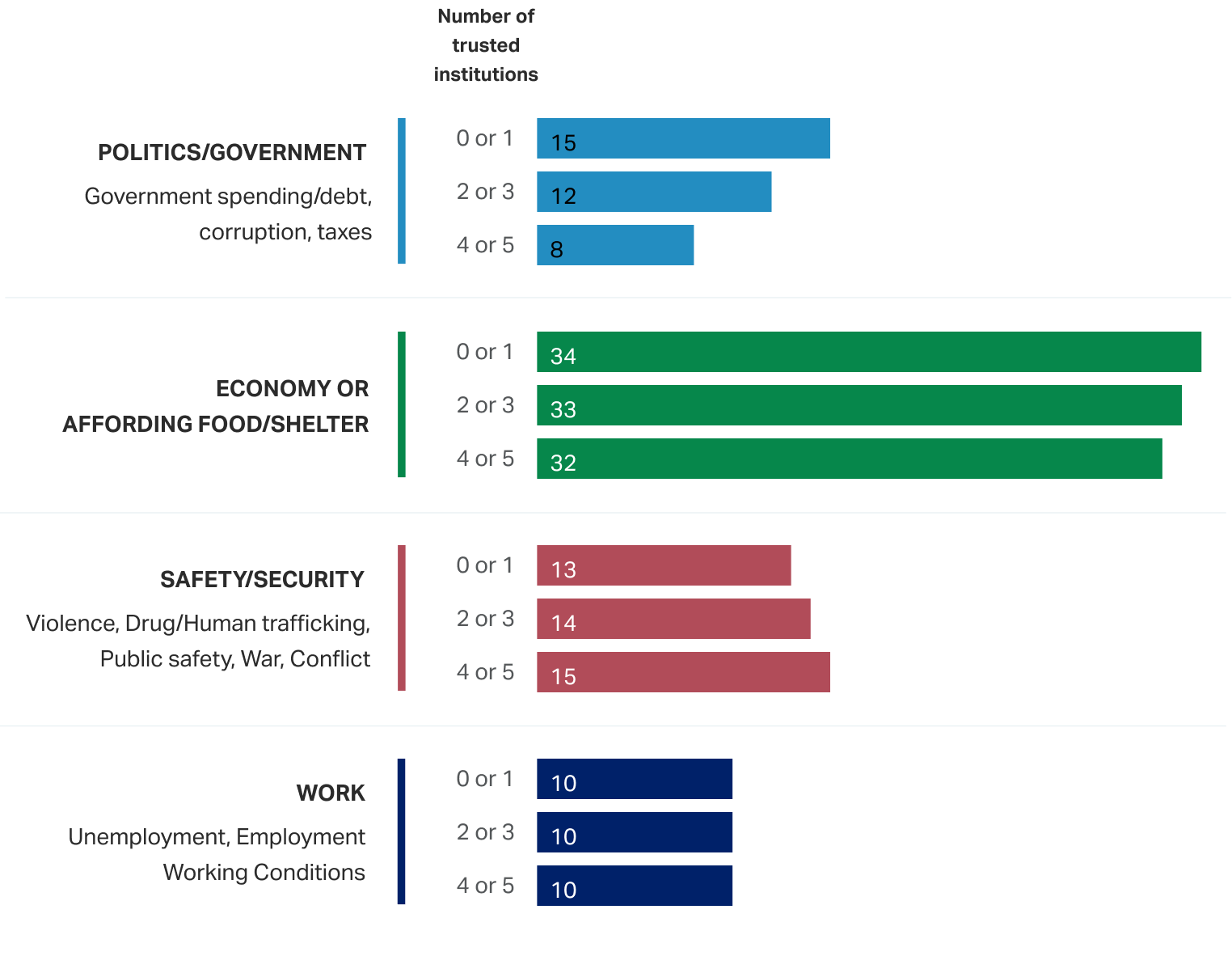

Institutional trust is uniquely linked to national political satisfaction. People expressing low confidence in institutions — such as the national government, the judicial system, election integrity, the military and financial institutions — are more likely to identify politics as their country's biggest problem.

After controlling for other demographic factors and national income, people who express trust in none or just one of these five institutions are roughly twice as likely to say that politics is the biggest national problem as those who are confident in four or five institutions (15% vs. 8% respectively).

Notably, institutional confidence shows little relationship to whether people cite the economy, employment or safety/security as top concerns.

Perceived Top National Problem by Level of Institutional Trust (% medians)

Bar chart showing that adults with low trust in institutions are nearly twice as likely to cite politics as their country’s top problem (15% vs. 8%). Trust in institutions has less influence on views of economic issues, safety and security, and work-related issues as the most important problem in one’s country.

Data are cut by the number (of five) institutions that respondents have confidence in: national government, judicial system, honesty of elections, military and financial institutions. The percentages presented in these charts are estimated marginal means generated from general linear regression models, which control for a range of respondent demographic characteristics and country-level attributes. These include respondent age, gender, household income level, education, urbanicity, marital status, employment status and life evaluation. Country-level metrics include GDP growth, unemployment rate and World Bank income classification.

The relationship between confidence in institutions and perceived problems in national governance is strongest in high-income countries. In lower-income nations, this relationship largely disappears, as political frustration may be overshadowed by economic hardship or normalized as part of daily life.

In 11 high-income countries, there are double-digit gaps between individuals with high vs. low trust in institutions in their belief that politics/government is the most important problem in their country. These gaps are widest in Hungary (26 points), Finland (21 points), the U.S. (20 points), the Czech Republic (19 points) and Canada (19 points).

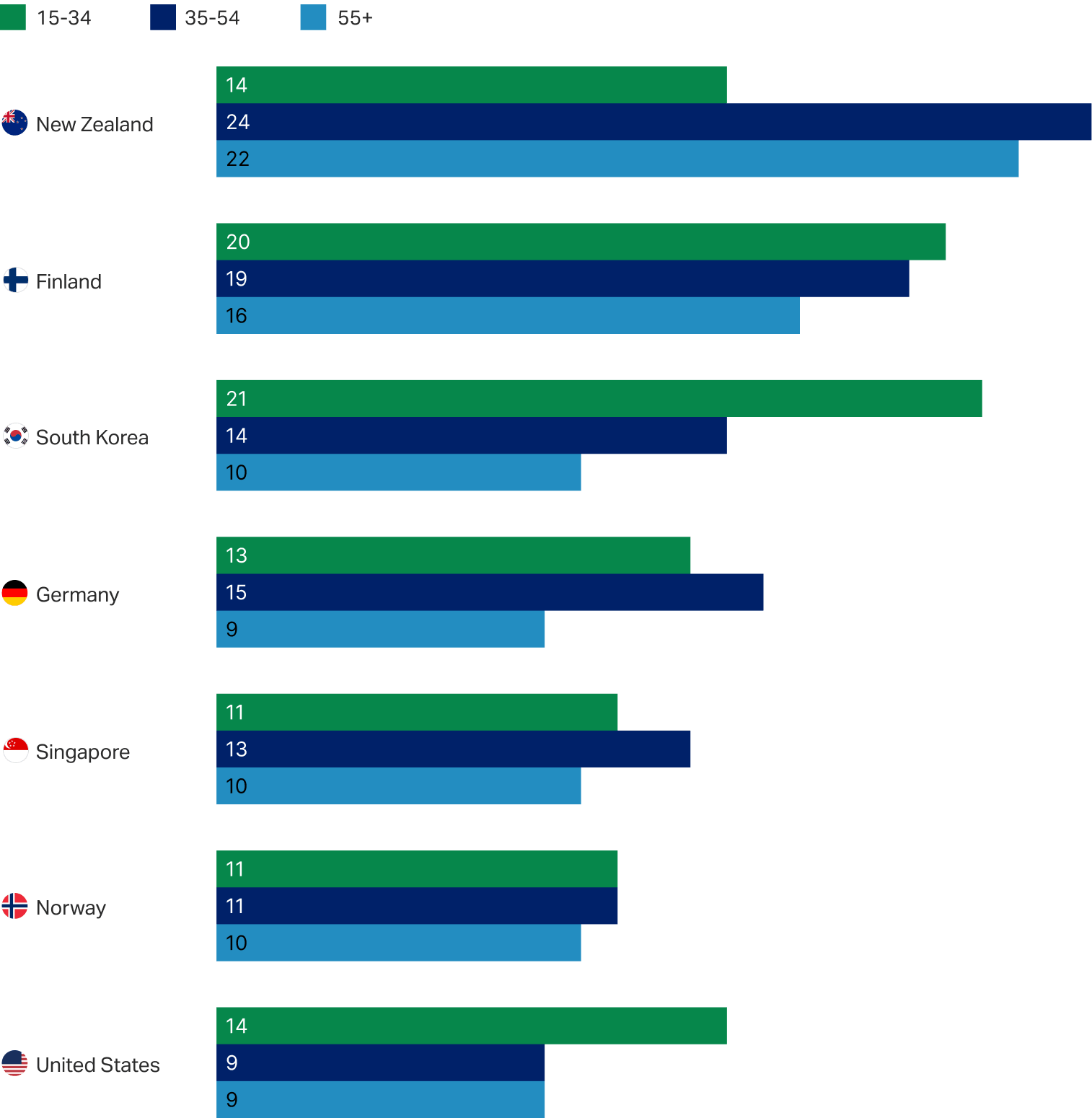

Go Deeper: Concern Spans Generations Where Social Issues Rank High

Social issues such as discrimination, racism and poverty do not rank among the top national problems globally. However, they spark relatively high concern in several high-income countries, including New Zealand (20%), Finland (18%), South Korea (15%), Germany (12%), and Singapore, Norway and the U.S. (all 11%).

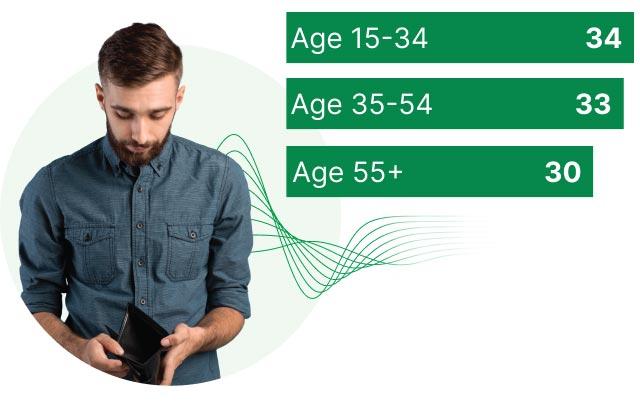

In these countries, concern about social issues spans generations. Similar proportions of younger and older adults identify social issues as their country's biggest problem, challenging the assumption that such concerns are concentrated among youth.

Bar chart displaying the percentage who perceive social issues to be the top concern in their country by age group. Countries shown include New Zealand, Finland, South Korea, Germany, Singapore, Norway and the United States. At least 10% of the youngest age group, those 15-34, see social issues as a top problem in all seven countries.

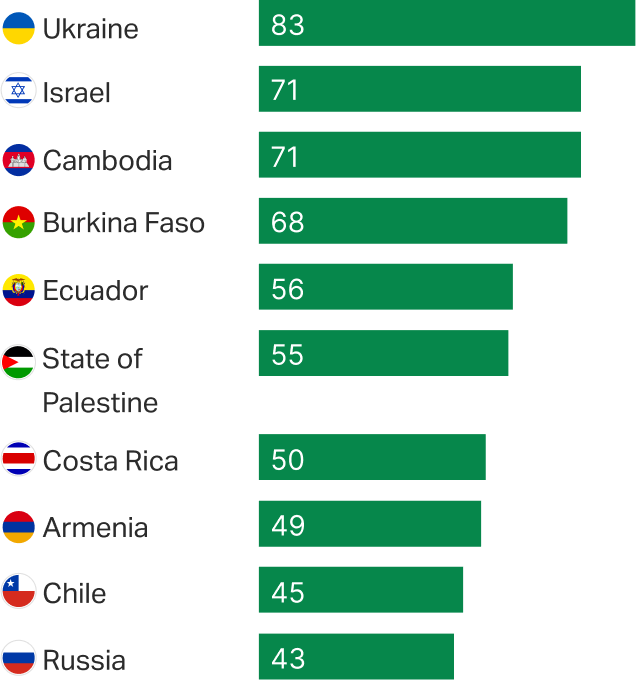

Go Deeper: Concern About Immigration in High-Income Countries

At the global level, other national priorities often outweigh concerns about immigration.

Key Insight

Across 107 countries, a median of just 1% name immigration as their top national issue.

Concerns about migration cluster in high-income countries that often serve as target destinations for those seeking to move, including the United Kingdom, where 21% name immigration as the biggest national problem, the Netherlands and Cyprus (both 13%), and Portugal and Malta (both 12%).

However, in countries where at least 5% of adults cite immigration as the top national problem, there is little relationship to total migration levels.

-

The United Kingdom stands out for its high levels of concern despite having a similar share of foreign-born residents as the U.S., Sweden and Norway — all of which see much lower levels of concern about immigration relative to other national issues.

-

Similarly, comparable proportions of adults in Malta and the Dominican Republic name immigration as their top issue (12% and 11% respectively), even though Malta has six times the proportion of immigrants.

These comparisons highlight a recurring pattern:

-

In countries where immigration rises to the top of national concerns, public debate is often disconnected from actual migration levels and shaped instead by wider political, historical and media contexts.

What This Means for Leaders

Political dissatisfaction tends to concentrate in prosperous democracies where open criticism of government is a part of civic life.

Some of this discontent can be constructive, as healthy democracies depend on skepticism; however, there is a line beyond which it bleeds into a sense that the broader system is no longer working or self-correcting.

In higher-income countries, political concern is closely related to declining institutional trust and perceptions of whether institutions operate honestly and fairly.

Gallup research finds that how people feel about their local conditions and services, such as housing, healthcare and education, is the strongest predictor of institutional confidence. This relationship holds regardless of political system or national income.

If leaders want to build trust and demonstrate that politics works for ordinary residents, they need to start at the local level. The broader lesson for governments is that to be perceived as a solution, rather than a problem or roadblock, people must feel that the state is working effectively and fairly for them.