The following is an excerpt from Blind Spot, Gallup's new book about the rising unhappiness leaders didn't see. For more insights like this, order your copy of Blind Spot today.

"No man is happy who does not think himself so." (Publilius Syrus, first century B.C. Latin writer)

On a fall day in 2009, my morning started in a conference room in a midtown Manhattan office. You could see the famous Radio City Music Hall sign from the 23rd-floor window.

I was there to meet with a foundation Gallup was working with to study hunger in Africa. The foundation had retained a university professor to advise us on the study, and he was there as well.

Everything went as planned and nothing about the meeting was particularly noteworthy, except for one thing -- an exchange between the professor and me.

For months, I had encouraged the foundation to include questions about wellbeing in their hunger survey. I brought it up again in this meeting, hoping they would finally use these items. The professor -- who had never liked the idea -- reiterated that they did not want to ask wellbeing questions in the survey. I still could not figure out why, so I asked him.

He didn't think twice about the question and replied, "We want to make sure that Africans don't say they are happier than they really are."

There it was. The professor was concerned that Africans could not accurately describe how their lives are going.

Except Africans -- and all people -- do know how their lives are going. And they can accurately describe their lives to anyone who asks them. This is why we use surveys to measure wellbeing -- to understand how people's lives are going, we need to hear from people themselves.

How Accurate Are Happiness Surveys?

Many people believe that surveys capture "soft" data and that the only reliable data are "hard" metrics such as unemployment. They blindly trust labor force statistics and never ask, "How is that information collected?"

If you ask people how they think unemployment data are collected, they say it is based on a headcount or by tallying the number of people receiving unemployment benefits. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the agency responsible for these indicators, addresses those issues verbatim:

Some people think that to get these figures on unemployment, the government uses the number of people collecting unemployment insurance (UI) benefits under state or federal government programs. …

Other people think that the government counts every unemployed person each month. …

Because unemployment insurance records relate only to people who have applied for such benefits, and since it is impractical to count every unemployed person each month, the government conducts a monthly survey called the Current Population Survey (CPS) to measure the extent of unemployment in the country.

So even many "hard" metrics such as unemployment are captured by a survey. Most countries conduct a labor force survey at least once per year; wealthier countries measure unemployment even more frequently. The survey is administered by a government agency or ministry, such as the BLS.

The BLS conducts a household survey of around 60,000 people every month. Interviews are conducted in person and over the phone, similar to how pollsters call people during elections to ask who they intend to vote for.

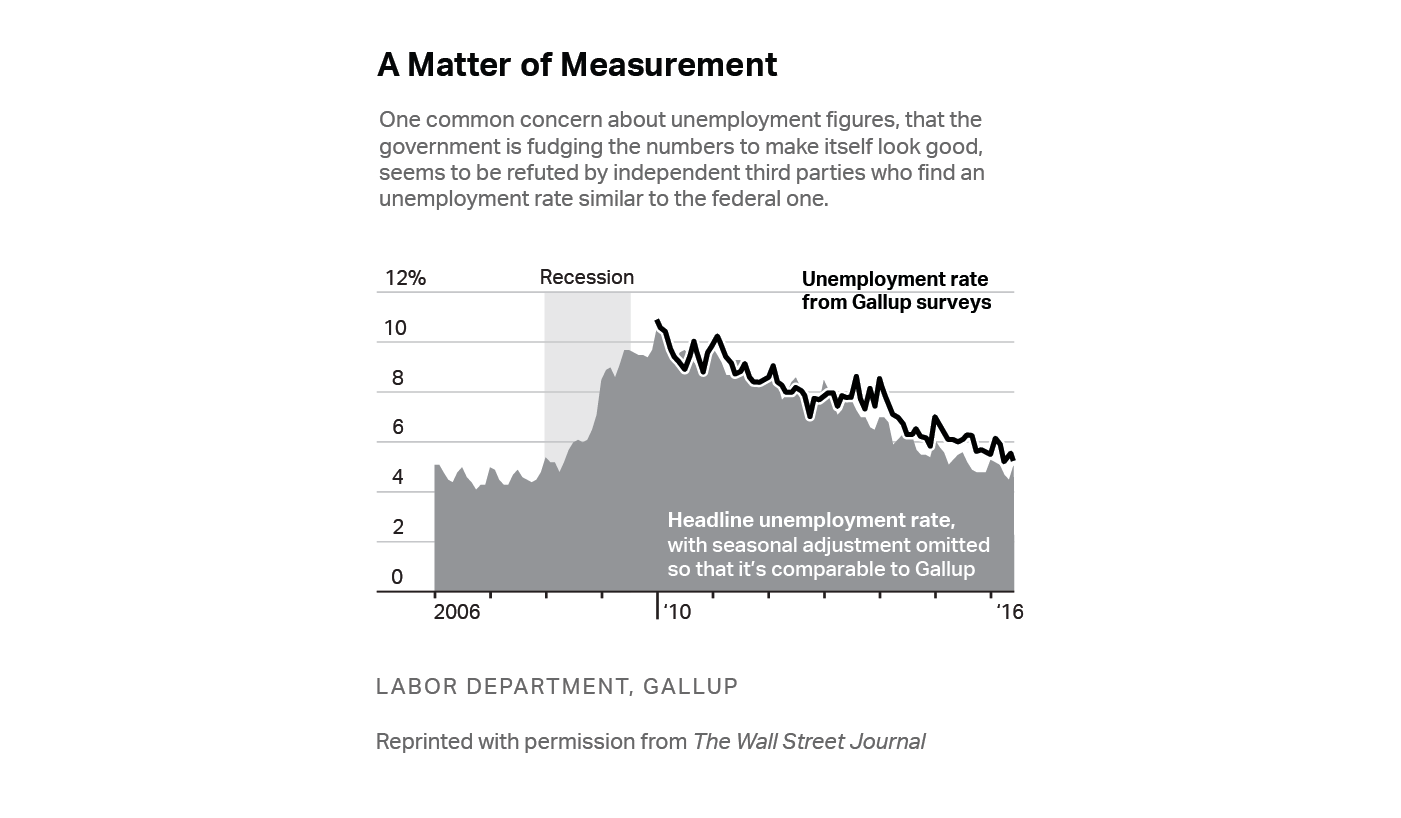

The measures are reliable. In fact, you can independently verify them using nongovernment statistics, such as Gallup's U.S. unemployment data, which are collected using a similar methodology. In 2016, The Wall Street Journal showed just how closely Gallup's daily tracking of U.S. unemployment follows the BLS' figures on unemployment.

Custom graphic. Chart representing how figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics mirror figures from Gallups trend on unemployment, from 2006 to 2016.

Although they have methodological differences, both are still surveys. For wellbeing statistics, instead of asking people if they have a job, we simply ask them how their lives are going.

Many people trust survey methodology -- it is the questions they do not like. They think asking if someone has a job is useful for leaders, but asking about policy on climate change or healthcare is not because people often are not fully informed on the issues.

Critics cite research that tests people's basic knowledge of civics. For example, Gallup once asked Americans: "As far as you know, from what country did America gain its independence following the Revolutionary War?" Nearly 20% of Americans did not know. We even conducted the survey not long before the Fourth of July. In fact, 13% of Americans were not even sure what the country celebrates on July Fourth.

Pundits denounce the "wisdom of crowds" based on this reasoning. If the public does not understand American history, why trust their judgment on issues like healthcare, immigration, or going to war?

But people's opinions still count -- whether or not those opinions are informed. Additionally, people make decisions based on what they believe, so there is value in knowing what they believe, regardless of how well-informed they are.

Whatever the case, understanding a country's history or a country's plan for healthcare is different from knowing your own life. People may not be experts on history, science, or current events, but they are the best experts in the world on their own lives.

People make decisions based on what they believe, so there is value in knowing what they believe, regardless of how well-informed they are.

Former Gallup Regional Director Jihad Fakhreddine once interviewed a man in Lebanon and asked him how his life was going. The man replied, "A survey about my life! It is tar!" (He used the Arabic word zeft.) For Lebanese, "tar" or "asphalt" is a term that means things cannot be any darker -- he is living the worst life imaginable. According to Jihad, the way this man described his life, coupled with his desperate facial expression, meant "No need to ask me dozens of questions to know how I am doing." The point is, that man knew how his life was going.

But if for some reason you do not believe this man, you can actually audit his wellbeing. Just ask the people he spends the most time with. Researchers began asking people's friends and family, "How would this person rate their life?" Time and time again, their friends and family knew.

The professor I mentioned earlier was probably not just wrong on philosophical or moral grounds, he is also statistically wrong. These metrics can also be audited using objective indicators. For example, life evaluation and life expectancy highly correlate, meaning countries where people rate their lives the highest are also where people live the longest.

How Gallup Asks the World About Wellbeing

Wellbeing is measurable. But it is not easy to measure it everywhere.

In some countries, it is too dangerous for us to do our work. That's because in most countries, Gallup conducts interviews in person. An interviewer literally knocks on someone's door and asks them a series of questions. If a country descends into war, experiences a disease outbreak, or suffers from a natural disaster, we may have to change how we interview or stop interviewing altogether. For example, in countries where it may be unsafe to go door to door, we can do phone interviews instead. In fact, in the roughly 40 countries where we do not conduct face-to-face interviews, we conduct interviews over the phone.

The people who conduct interviews in these countries are locals. Kenyans interview Kenyans; Brazilians interview Brazilians. The photograph below shows an interview being conducted in Indonesia.

Photograph. Black and white photograph of a Gallup interviewer asking a respondent questions.

The last major barrier to conducting surveys is politics. We have never conducted interviews in North Korea. Imagine Gallup approaching the Central Bureau of Statistics in North Korea to get permission to do a wellbeing survey. Even if Kim Jong Un approved such a study, Gallup would still not be able to conduct the survey. As a U.S.-based organization, we must follow U.S. laws, including the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, which says that if we have sanctions on a country such as North Korea, we cannot hire people there to conduct interviews.

So that is how Gallup collects wellbeing and happiness data worldwide. From the World Happiness Report to the Arab uprising trends we discussed earlier -- they are all the same data, and we collect those data using the most robust methodologies in the world.