Story Highlights

- Equifinality means a result can be achieved in many different ways

- Some goals are best met with standard procedures; others with innovation

- Considering the equifinality spectrum improves engagement and performance

How do you help a team member facing a difficult conversation with an underperforming subordinate? How do you help an employee input data into your new HRIS?

If your approach to both scenarios is similar, it's time to rethink your approach to equifinality.

That may not be a word in your lexicon -- it's pretty uncommon. It means that a result can be achieved in many different ways. Though you may not use the word, judging when to use equifinality is probably part of the way you practice leadership.

You can practice equifinality better by being more deliberate with it -- and by understanding the strengths of your employees as well as the demands of their work.

Too little equifinality is boring. Too much is confusing.

Good leaders understand when to tell their employees to use any of "many possible means" and when to prescribe just one. They know when employees should lean into their strengths and when they should follow standard procedure. They know that while a difficult conversation can be approached in a variety of ways, there should be a process in place for data entry.

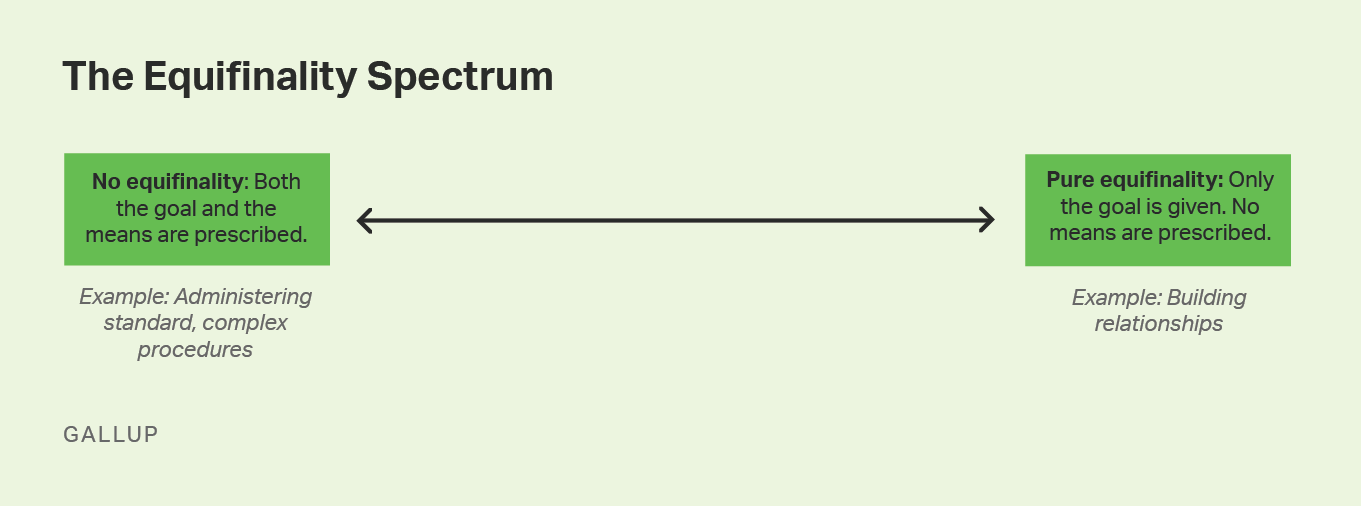

Great leaders are masters of assessing where needs fall on the equifinality spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is no equifinality, when both the goal and the means are prescribed. On the other end is pure equifinality, when only the goal is given.

Organizations waste thousands of hours not prescribing the means when they should, and overprescribing when they shouldn't.

Too little equifinality bores employees and prevents them from doing what they do best ("We're not robots!"). Too much equifinality confuses workers and makes their expectations unclear ("But how do you want it done?"). Either way, organizations underperform their potential and disengage their workers.

To unlock their people's potential, leaders must assess where each desired outcome falls on the equifinality spectrum. Average leaders over- or under-apply equifinality, without understanding the nuances and requirements of the job. They spend their time on one end or the other of the equifinality spectrum.

Good leaders understand when to tell their employees to use any of "many possible means" and when to prescribe just one.

The best leaders understand that in some situations, the only direction they should give is the goal. Particularly when the goal relates to relationships, employees will perform best when they can respond -- to, say, a client -- as they see fit. Anything else feels like handcuffs … confining and unhelpful.

In other situations, leaders should be much more prescriptive about the means of achieving the goal. If there is one best way for employees to enter data into a system, for example, leaders should provide the process and procedural steps required. Anything less sets the employee up to fail.

Organizational performance is optimized when leaders situate goals appropriately on the equifinality spectrum.

The best leaders know that for any intended outcome, they must first find its place on the equifinality spectrum. They constantly seek to understand both the project and person better, asking themselves the right questions.

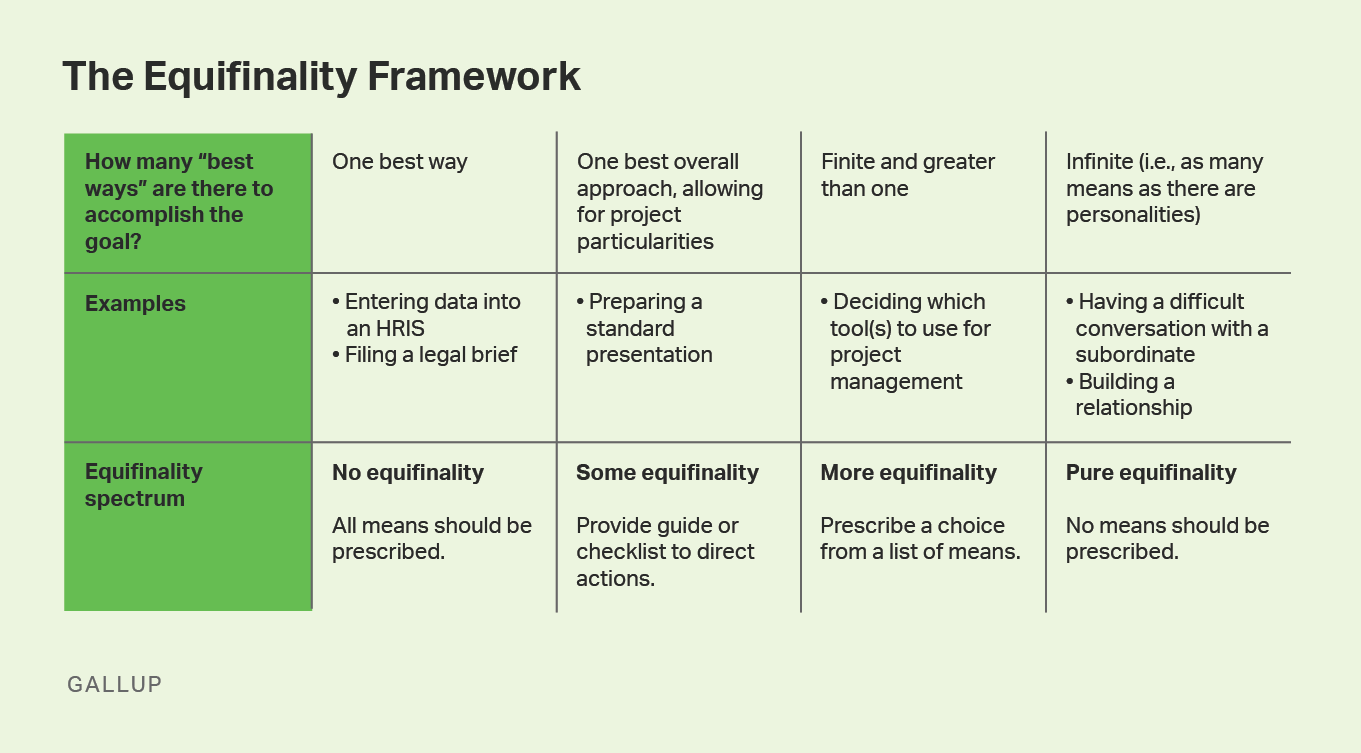

The grid below provides a framework for asking -- and answering -- these questions. Start by asking how many "best ways" there are to accomplish the goal at hand. If there is only one best way, such as for entering data into an HRIS or filing a legal brief, leaders shouldn't shy away from prescribing the steps to be taken. These tasks fall on the no equifinality end of the spectrum, because there's already an ideal methodology.

If there is one best overall approach that allows for project particularities, slightly more equifinality comes into play. For instance, if an employee is preparing a standard presentation, leaders should guide them with a checklist of questions to direct their actions, such as "Is a branded slide deck required? If yes, submit a design form to the design lead."

When there are multiple ways to accomplish a goal, but the list is finite, leaders ought to prescribe a choice from a list of means. For example, when helping their teams decide which project management tool to use, leaders could provide a list of possible tools from which to choose.

Finally, tasks fall on the pure equifinality end of the spectrum when there are infinite means to accomplish a goal. For tasks like having a difficult conversation with a subordinate or building a relationship, leaders can provide guidance through broad rules of thumb (e.g., "Be mindful of tone and facial expressions") but should give employees complete agency in deciding their approach. There are as many possibilities as there are personalities.

Leaders are more likely to maximize their human capital when they strike the right balance on the equifinality spectrum. They will be prescriptive enough to give clear direction when it's needed, and means-agnostic enough to let their people use their strengths when that's most effective.

Focus on finding the right place on the equifinality spectrum, and you will save your people thousands of hours of work, increase their engagement and optimize your organization's performance.

Start striking the right balance of equifinality to help employees perform at their best:

- Enroll in Leading High-Performance Teams and learn everything Gallup knows about how to create and sustain high employee performance.

- Partner with Gallup to evaluate your engagement strategy and focus on development.

- Position the best talent for the right role, especially when it comes to managers.